23.02.2023

This interview first appeared in the magazine accompanying the exhibition THE FINAL BID. You will find more illustrations in the magazine. The magazine is available free of charge at the museum. The interview was conducted by curators Birte Hinrichsen (BH) and Nicole Roth (NR) with artist Michael Pinsky (MP).

BH: Michael, we are delighted to talk to you today in more depth about your exhibition THE FINAL BID and to explore the themes and artistic considerations behind the work lending the show its title. Would you like to tell us how the idea for this large-scale installation came about?

MP: I first started to conceptualize the project THE FINAL BID whilst I was under- taking a residency in Norway with a group of environmental psychologists. (1)

I developed about fifteen ideas at the time, in response to conversations with the psychologists who were studying how art can change people’s perceptions of climate change. I then whittled these ideas down to just two. One was the POLLUTION PODS, which was essentially a dystopian idea, exploring how air pollution affects our everyday life and how the causes of air pollution are very similar to the causes of climate change (fig. 1). I used air pollution as a back door into discussions around climate change and how we could change people’s lifestyles. At the same time, I was trying to think of positive ways of encouraging lifestyle change. I started to think about the supply chain and the difference between recycling and reuse. Recycling—like net zero—is a bit of an excuse. The principles supporting net zero allow us to continue life as normal, mitigating travel by plane through planting trees, for example. Recycling is the same. When your purchases come in lots of recyclable packaging, you think, “Okay, that’s fine.” But recycling takes an enormous amount of energy, mostly supplied by fossil fuels, and this leads to a massive carbon output. So, we need to be thinking about how to reduce our consumption of goods at source, which means that we don’t need to recycle them. We should either use things for a long time because they’re well made, or reuse them, encouraging a circular rather than a linear economy. This is where the core concept for THE FINAL BID started to develop. I wanted to encourage people through an artwork to purchase goods secondhand and put the things that are sitting around them reused. We have lots of things around us that we don’t use, yet at the same time, these things are being produced from scratch using raw materials.

.png?locale=en)

BH: In one of our first conversations about THE FINAL BID, you discussed how mate- rials like wood, when taken out of the supply chain for a while, actually increase in market value. How did you get involved with this aspect? And can a connection to THE FINAL BID be drawn here?

MP: At the moment I’m working on a project that explores the supply chain of wood in the city of Leeds, England. I am diverting the wood out of the supply chain after its first rough cut, and then putting it back in the supply chain after it has aged for a year and gained value as weathered wood (fig. 2). I recently presented this work to Leeds Beckett University, a partner in this project. They had just moved from their old art college, which was full of furniture, to a new building, and every single bit of furniture in the building was brand new. I was looking at all these new chairs which were made from plastic, chrome, steel, and padding fabric, all combined into one piece of furniture and incredibly difficult to recycle. The tables were all made from laminates with various types of plastic and had steel legs with plastic wheels on the bottom. Again, in- credibly difficult to recycle. So, I asked the question: “Who made this decision? You have moved into a new building, which I can understand, as you have probably sold the old building, but what happened to the furniture? Did anyone think, ‘Shall we take this old furniture with us?’” There wasn’t a person in the room who could say what had happened to the old furniture. Is it now in a landfill? Was it sold?

The supply chain is the poor cousin of the climate change debate. We think about transportation, we think about energy, to some extent we think about insulation, but we don’t think about the massive impact that buying new goods has on the environment. Why do we buy new chairs when our old ones might not be the most fashionable but are perfectly functional?

.png?locale=en)

NR: To take a more concrete look at your art installation THE FINAL BID: people were asked to bring chairs that they no longer use or want to the museum. Museum visitors, as well as Internet users, can bid on these chairs in an auction that takes place throughout the duration of the exhibition. Through the bids, the chairs are pulled up into the exhibition space and form a moving installation. Was the original idea exclusively focused on used chairs?

MP: My original idea was to have a single hanging structure which would host objects that would change every month. So, it could be chairs for one month, then bicycles the next month, followed by curtains, and then lights. Each month, the host organization would advertise a request for particular products, by type, color, or shape. However, the proportions of the Draiflessen Collection necessitated another approach, with a number of these hanging structures rather than a single one. My first thought was to have each hanging structure support a different type of object, but after some conversations with the Draiflessen team I decided to focus on the chair, which could symbolize any of our unwanted and unused goods.

BH: It is fascinating to see the points of reference that the object of the chair offers. On the one hand you have this very normal use of a chair—you sit on it, and you can typically use it for a very long time. Despite this, or maybe precisely because of this, it became kind of a trend— obviously pushed by marketing in big furniture stores—to refurnish your home every year and decorate it in a different style each season. On the other hand, the chair is a very iconic object that designers and artists have dealt with again and again. But which aspects are of particular interest to you in this art project or as an artist—not just in the object “chair,” but in the handling of everyday objects in general? Art-historical references like the readymade or the objet trouvé come to mind. In your opinion, does THE FINAL BID suggest an alternative way of dealing with objects of consumption in our everyday lives?

MP: The concept of the ready-made is key to this project. Take Marcel Duchamp’s urinal (Fountain, 1917), for example.

NR: I think it is obvious that for you the artwork is a way of bringing people into action, of activating them. The installation will only work if people bring us their chairs, and if they want to buy chairs. It is all about people becoming involved.

MP: This is true, and this is why this project is risky. When you build a sculpture, you can control its appearance. With THE FINAL BID, we don’t know what chairs will be offered, so we don’t know how the installation will look. As with John Cage’s systems of chance, we have no idea how the arrangement of chairs will be composed. It’s entirely dependent on the public, both to supply the exhibition and to engage with it, and this is unpredictable.

My ambition with THE FINAL BID is to encourage visitors to change their lifestyles by creating new habits. This is only symbolic at this point, but the installation demonstrates that new habits are possible.

You establish new patterns of behavior through action, not by talking. Using David Kolb’s learning model, firstly you experience the work, then you reflect on its form, then you consider the systems which underpin the work, and finally you actively engage in the process. Only at the point of action do you embed the learning. This relates to a project that I’m curating in King’s Cross, called The Natural Cycle, by the artist Roadsworth. It is a mini-village of roads which helps young children to learn how to cycle. It lets them build a sensibility around the roads; where you give way, how you cross the road, how you turn right, how you turn left, and how you deal with zebra crossings. It familiarizes them with the whole vernacular of the street, the road signage and markings, be- fore they cycle on a real street. If you build certain habits as a child, you tend to keep those habits for the rest of your life. If you’re used to being driven to school every day as a child, you will probably continue to drive. That’s your norm. But if you cycle to school, you are likely to cycle as an adult. Thus, it is essential to establish those habits with children when they are young. This will have a significant impact on our climate. So, The Natural Cycle establishes patterns of behavior through action at a really young age.

In a similar way, THE FINAL BID helps children to reevaluate the assumption that new is good, and to consider whether new should be bad and old is good. I want children to ask their parents, “Why are you buying new chairs? The ones we have

BH: This is an interesting example, as I recently saw on Instagram that it is supposedly better to buy a new fridge if the used one is very old. But how do I know that’s true, and how can I take all factors into account and not just electricity consumption?

MP: We have the same dilemma with electric cars. People buying electric cars feel really good about themselves, but if that means making a new car from scratch, how many years do you need to run that car be- fore its lower carbon footprint in terms of fuel consumption outweighs the carbon cost of its production? We were subsidized by governments to move from petrol cars to diesel cars due to the lower carbon output, only to find out later that we had been deceived by companies such as Volkswagen about their cars’ toxic emissions. Then everybody switched back to petrol cars. All new cars, great for the car manufacturers creating massive new markets. Now we are transitioning to electric cars. Again, everyone is disposing of old cars and buying new cars, again fantastic for car manufacturers. The option of getting rid of the private car altogether is rarely considered. It is bad for the market. It is bad for capitalism. It is the same with computer monitors and TVs. Everyone replaced them with the flat-screen ones, and the “fat” old ones got thrown out even though they were still working. I’ve got speakers in my studio that I bought secondhand thirty-five years ago, and they still work perfectly. Technology is one of these areas where people have to buy again and again, as the software stops being supported and the interconnecting plugs become redundant. The manufacturing industry maintains a market where they actively make existing technology obsolete to sell new gadgets.

BH: And creating a sense of lack or need is obviously a big part of it, isn’t it? That constant feeling of need. You need something, and you especially need something new. This feeling is not only conveyed through advertising and trends, but the need is artificially created by products—especially technical ones—breaking down after a certain time. I’m sure you know what this

NR: And what about art? Are you convinced that artworks can bring people to change their habits?

MP: I’m doing what I can do within my profession as an artist. I won’t have as much impact as a politician or a CEO of a big manufacturing company, but my art can symbolically demonstrate principles. Art is shown in a privileged framework. People go to galleries and museums to think and reflect. You’re not grabbing them on the street, you’re not in a newspaper full of adverts, you’re not in a Twitter feed. The opening of the mind that happens in a gallery or museum is a unique moment that artists have access to. During these reflective moments, people can genuinely absorb information in a creative way, and rethink how they are living their lives. So, artists do have an important role in terms of changing the culture around consumer- ism, because our currency is our culture.

BH: That is a very important point and an intriguing analogy. From a curatorial point of view, our approach from the very beginning was to pursue a thematic issue for the exhibition. The Draiflessen Collection is currently dealing intensively with questions of sustainability and thus also with the ideal of a green museum. The issues you explore in your work naturally fit in very well with this. Would you like to tell us more about which themes and questions are important to you and what interests you as an artist?

MP: Even as a child I took a keen interest in the environment before I knew anything about climate change. When I was about eight years old, the local museum hosted an exhibition sponsored by Scottish nuclear power. It was a pseudoscientific exhibition about nuclear reactors, demonstrating how good they were and how they gave us “free” energy. I was adamantly opposed to nuclear energy at that age. There were no sustainable solutions around waste disposal, and there still aren’t. So, I visited the show with my friends and kept on asking the tour guides difficult questions. We must have looked incredibly precocious at the time, and we ended up getting thrown out. However, we kept on returning until they wouldn’t even let us in the exhibition. I was astutely aware, even as a child, that this exhibition was greenwashing nuclear power. Since then, I have continued with this activism. As an art student, my work was very much in the vein of British Land Art. I was inspired by artists such as Richard Long, Andy Goldsworthy, Kate Whiteford, and David Nash. My work focused on the countryside. But when I moved to London, I started to feel that this approach was a romantic irrelevance. The everyday environment in which most people live is urban, not rural.

I found it bizarre that people drove everywhere in London in cars. This was at a time when the Conservative Party had destroyed the public transport infrastructure. So, I started to map out central London by recording the time it took to drive, cycle, walk, take the bus and the Tube. I designed temporal maps comparing the modes of transport to show how long it took to drive and how ridiculous it was (fig. 4). I showed these hybrid map/prints in a gallery within The Economist building in central London. The exhibition led to a lively discourse around why the existing communications systems promoted the use of the car and the Tube, rather than walking and cycling. In the center of London, riding the Tube can take longer than walking, because you need to descend far underground just to get to the platform. To make the right choices we need to have the right information. At that time there was no data about how long it took you to get from A to B.

BH: Absolutely. An exciting thought—especially as a cyclist.

MP: The GPS systems only show you how long it takes to drive from A to B, but not how long it takes to park. With all the da- ta they collect in the cloud, this would be easy to provide.

BH: I find it interesting that people are un- aware of how much time is actually spent looking for a parking space, although there are even statistical surveys on this. In Germany, drivers spend an average of forty-one hours a year looking for a parking space—that’s almost two days! (2)

MP: This shows again how all of these things are interlinked. The data exists, but the data is manipulated or obscured to encourage consumption. So, we need art to provide the counternarratives. We live in a neoliberal economy that promotes consumption. Governments are always trying to increase their gross domestic product. Art offers a rare opportunity to counteract that political force, because the narrative that economic growth is good is being sold to us every day. Governments will not pro- mote degrowth, and of course manufacturers will not support this, as they see it as economic suicide. So, who’s going to do it? Institutions such as museums need to host artists who question this current “consume until you eat yourself” crisis that we’re in.

BH: And there we are again with the change in human behavior and the need for a sustainable lifestyle. Because at the moment, Germans are consuming the re- sources of almost three earths on a global scale. Anyone can see at a glance that this is too much: we only have one earth. It is as simple as that. (3)

Obviously, a participatory aspect is an important part of your artistic practice. Instead of just researching data for your works of art, you are pursuing a more collective way of working with people; maybe you raise a question that frames an art project, but people will create the data while interacting within your framework. So it’s more like creating a new narrative together in a way.

MP: It is. People are implicit in this narrative; whether I can change things or not is another matter—one can only try. Some of the visitors to my show at The Economist told me that they would return home a different way from the way they had arrived. That is behavioral change, which is something that is really important in my work. It is behavioral change through action. Firstly, you have to change people’s perceptions; then they need to change their behavior through changing their actions. This is one of the goals of my work. But, of course, I never want to undermine the aesthetic qualities of my work. I am playing that very fine line between something that is visually arresting and important within the cannon of art history, and something which changes people’s behavior. The work could easily slip off the line and become solely propaganda. Maintaining a strong visual sensibility is essential to carrying the narrative of the artwork. It is the powerful visual moment that engages people in the first place. It is what lures people in. Then the narrative is revealed.

BH: To conclude our conversation, allow me to ask a somewhat heretical question: What is actually the artwork in this exhibition? Is it the idea or the installation? And what about the visitors’ additions?

MP: The framing of the installation within the museum space clearly articulates it as an artwork. This question is more challenging when my installations are in the public realm, where the context is more ambiguous. Engaged practice and relational aesthetics are familiar terms within the sphere of professional art, but not for the general public. However, the journey to the exhibition space at the Draiflessen Collection—through the garden, down the ramp, through the shop, up the steps—provides an expansive threshold which is telling the visitor, “You are going to see an artwork.” So, by the time they get up those steps, they are primed to experience art, even if they are looking at their old chair which was in the cellar a couple of weeks before. Again, this goes back to Duchamp, the framing of the object and the intention of the artist. I have no doubt that this is an artwork. For me, what makes THE FINAL BID intriguing are the engagement and narrative aspects of the work, beyond its physical manifestation. Just hanging a bunch of chairs on wires isn’t interesting to me. It’s everything else that makes the artwork compelling.

_______________________________________________________________

(1) Climart, https://www.climart.info/ (all URLs accessed in August 2022).

(2) Hedda Nier, “So lange sind die Deutschen auf Parkplatzsuche,” Statista, August 2, 2017, https://de.statista.com/ infografik/10532/so-lange-sind-die-deutschen-auf-parkplatzsuche/.

(3) “UNICEF-Bericht: Deutsche verbrauchen fast drei Erden,” Tagesschau, May 24, 2022, https://www.tagesschau.de/ ausland/unicef-ressourcen-verbrauch-101.html.

Interview with the artist Michael Pinsky

This interview first appeared in the magazine accompanying the exhibition THE FINAL BID. You will find more illustrations in the magazine. The magazine is available free of charge at the museum. The interview was conducted by curators Birte Hinrichsen (BH) and Nicole Roth (NR) with artist Michael Pinsky (MP).

BH: Michael, we are delighted to talk to you today in more depth about your exhibition THE FINAL BID and to explore the themes and artistic considerations behind the work lending the show its title. Would you like to tell us how the idea for this large-scale installation came about?

MP: I first started to conceptualize the project THE FINAL BID whilst I was under- taking a residency in Norway with a group of environmental psychologists. (1)

I developed about fifteen ideas at the time, in response to conversations with the psychologists who were studying how art can change people’s perceptions of climate change. I then whittled these ideas down to just two. One was the POLLUTION PODS, which was essentially a dystopian idea, exploring how air pollution affects our everyday life and how the causes of air pollution are very similar to the causes of climate change (fig. 1). I used air pollution as a back door into discussions around climate change and how we could change people’s lifestyles. At the same time, I was trying to think of positive ways of encouraging lifestyle change. I started to think about the supply chain and the difference between recycling and reuse. Recycling—like net zero—is a bit of an excuse. The principles supporting net zero allow us to continue life as normal, mitigating travel by plane through planting trees, for example. Recycling is the same. When your purchases come in lots of recyclable packaging, you think, “Okay, that’s fine.” But recycling takes an enormous amount of energy, mostly supplied by fossil fuels, and this leads to a massive carbon output. So, we need to be thinking about how to reduce our consumption of goods at source, which means that we don’t need to recycle them. We should either use things for a long time because they’re well made, or reuse them, encouraging a circular rather than a linear economy. This is where the core concept for THE FINAL BID started to develop. I wanted to encourage people through an artwork to purchase goods secondhand and put the things that are sitting around them reused. We have lots of things around us that we don’t use, yet at the same time, these things are being produced from scratch using raw materials.

.png?locale=en)

Michael Pinsky, Pollution Pods (2017), Projektzeichnung, Bleistift auf Millimeterpapier, 420 × 594 mm, (Abb. 1)

| © Michael Pinsky, Courtesy the artist

BH: In one of our first conversations about THE FINAL BID, you discussed how mate- rials like wood, when taken out of the supply chain for a while, actually increase in market value. How did you get involved with this aspect? And can a connection to THE FINAL BID be drawn here?

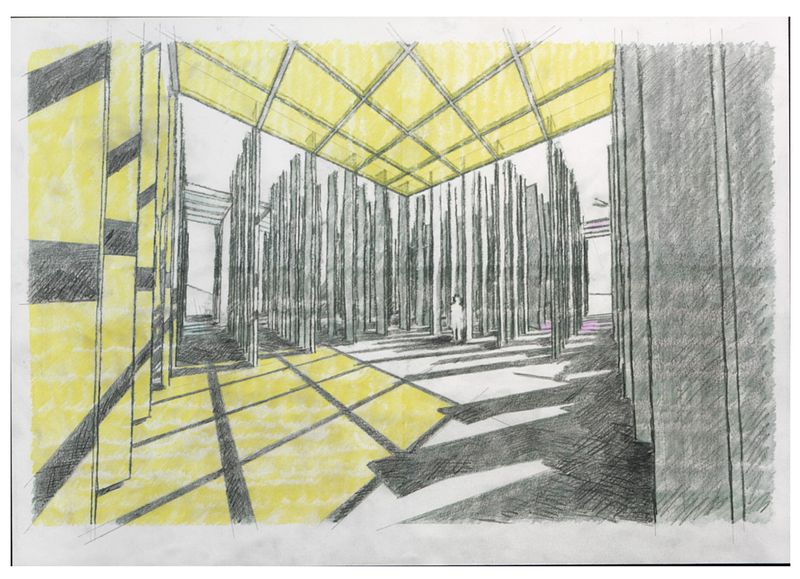

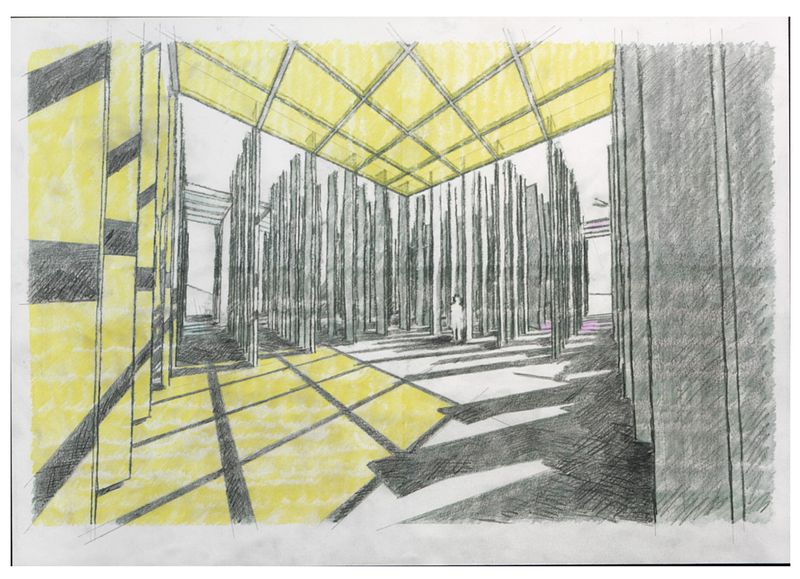

MP: At the moment I’m working on a project that explores the supply chain of wood in the city of Leeds, England. I am diverting the wood out of the supply chain after its first rough cut, and then putting it back in the supply chain after it has aged for a year and gained value as weathered wood (fig. 2). I recently presented this work to Leeds Beckett University, a partner in this project. They had just moved from their old art college, which was full of furniture, to a new building, and every single bit of furniture in the building was brand new. I was looking at all these new chairs which were made from plastic, chrome, steel, and padding fabric, all combined into one piece of furniture and incredibly difficult to recycle. The tables were all made from laminates with various types of plastic and had steel legs with plastic wheels on the bottom. Again, in- credibly difficult to recycle. So, I asked the question: “Who made this decision? You have moved into a new building, which I can understand, as you have probably sold the old building, but what happened to the furniture? Did anyone think, ‘Shall we take this old furniture with us?’” There wasn’t a person in the room who could say what had happened to the old furniture. Is it now in a landfill? Was it sold?

The supply chain is the poor cousin of the climate change debate. We think about transportation, we think about energy, to some extent we think about insulation, but we don’t think about the massive impact that buying new goods has on the environment. Why do we buy new chairs when our old ones might not be the most fashionable but are perfectly functional?

Michael Pinsky, Making A Stand (2022), Projektzeichnung, Buntstifte und Bleistift auf Papier, 420 × 594 mm, (Abb. 2)

| © Michael Pinsky, Courtesy the artist

So, returning to Norway, we had this moment in a room with these environmental-psychologists, and we were around a table. There was a huge argument about which of the two ideas we should pursue. Instinctively, I wanted to develop the POLLUTION PODS, the dystopian work mentioned above (fig. 3). I think it was appropriate at the time. But I still wanted to try a utopian approach.

BH: The exhibition THE FINAL BID now explores this utopian idea. We are delighted that you have decided to realize this idea at the Draiflessen Collection. But the great thing is that in November visitors will even have the opportunity to experience both ideas—the utopian and the dystopian—as we will also be showing the POLLUTION PODS on our premises for a few weeks.

BH: The exhibition THE FINAL BID now explores this utopian idea. We are delighted that you have decided to realize this idea at the Draiflessen Collection. But the great thing is that in November visitors will even have the opportunity to experience both ideas—the utopian and the dystopian—as we will also be showing the POLLUTION PODS on our premises for a few weeks.

But tell us a bit more about your installation THE FINAL BID.

MP: With THE FINAL BID, I am thinking about longevity in terms of every item we buy and about using the product until it completely falls apart. This is part of the style of the object. We often wear clothes until they look a bit worn, a bit tired, and then they go into the recycling chain. Textile recycling has a huge carbon footprint. But if it was stylish to wear everything until it was threadbare, our clothing could last for decades. We are addicted to buying clothes. In the United States, people buy on average one new item of clothing every five days. And yet I, in turn, still wear clothes I bought fifteen years ago. I wear them until they completely fall apart. Obviously, I’m not going to wear them to a fancy party, but if I’m working from home or gardening, they are fine. I have a hierarchy of clothes where they get more and more worn out until they are completely unusable. And again, furniture can last for decades and decades, possibly centuries. So, why are we still buying furniture? Perhaps we don’t even need to buy furniture anymore.

MP: With THE FINAL BID, I am thinking about longevity in terms of every item we buy and about using the product until it completely falls apart. This is part of the style of the object. We often wear clothes until they look a bit worn, a bit tired, and then they go into the recycling chain. Textile recycling has a huge carbon footprint. But if it was stylish to wear everything until it was threadbare, our clothing could last for decades. We are addicted to buying clothes. In the United States, people buy on average one new item of clothing every five days. And yet I, in turn, still wear clothes I bought fifteen years ago. I wear them until they completely fall apart. Obviously, I’m not going to wear them to a fancy party, but if I’m working from home or gardening, they are fine. I have a hierarchy of clothes where they get more and more worn out until they are completely unusable. And again, furniture can last for decades and decades, possibly centuries. So, why are we still buying furniture? Perhaps we don’t even need to buy furniture anymore.

.png?locale=en)

Michael Pinsky, Pollution Pods (2017), Norwegen, Mixed-Media-Installation, ø 18,03 m (gesamt), (Abb. 3)

| © Michael Pinsky, Courtesy the artist

NR: To take a more concrete look at your art installation THE FINAL BID: people were asked to bring chairs that they no longer use or want to the museum. Museum visitors, as well as Internet users, can bid on these chairs in an auction that takes place throughout the duration of the exhibition. Through the bids, the chairs are pulled up into the exhibition space and form a moving installation. Was the original idea exclusively focused on used chairs?

MP: My original idea was to have a single hanging structure which would host objects that would change every month. So, it could be chairs for one month, then bicycles the next month, followed by curtains, and then lights. Each month, the host organization would advertise a request for particular products, by type, color, or shape. However, the proportions of the Draiflessen Collection necessitated another approach, with a number of these hanging structures rather than a single one. My first thought was to have each hanging structure support a different type of object, but after some conversations with the Draiflessen team I decided to focus on the chair, which could symbolize any of our unwanted and unused goods.

BH: It is fascinating to see the points of reference that the object of the chair offers. On the one hand you have this very normal use of a chair—you sit on it, and you can typically use it for a very long time. Despite this, or maybe precisely because of this, it became kind of a trend— obviously pushed by marketing in big furniture stores—to refurnish your home every year and decorate it in a different style each season. On the other hand, the chair is a very iconic object that designers and artists have dealt with again and again. But which aspects are of particular interest to you in this art project or as an artist—not just in the object “chair,” but in the handling of everyday objects in general? Art-historical references like the readymade or the objet trouvé come to mind. In your opinion, does THE FINAL BID suggest an alternative way of dealing with objects of consumption in our everyday lives?

MP: The concept of the ready-made is key to this project. Take Marcel Duchamp’s urinal (Fountain, 1917), for example.

If the artist’s intention is that it’s art, then it’s art. The reversal of the urinal removes its original functionality. You can’t use it as a urinal in the museum. You can only look at it as a form in its own right, as a sculpture. But what happens when you take Duchamp’s urinal and stick it in a men’s toilet? Is it still an artwork, or is it just a urinal? Herein lies the fluid and somewhat ambiguous framing of our chair; we are removing it from its everyday context. It’s suspended. You cannot sit on it. You can’t even touch it. It is shown in the context of a museum. That is why the Draiflessen Collection is so relevant. It is not a contemporary art gallery, but a museum, which lends the chair a certain “gravitas.” However, once it is bought, the buyer has the option to show the chair as a sculpture or sit on it again. So, the object has only a temporary existence as a sculpture. It is fun to play with this ambiguity.

In Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965), there is a chair on the wall which you can’t use. There is a photograph and a text, all exploring the value systems between the mediation of the chair, the object itself, and the function of language. Which has more importance? The word chair, the actual chair, or the photograph of the chair? The chair has already been used to develop fundamental conversations around conceptual art and semiotics, so it is a great object to reference. A bicycle doesn’t have the same resonance. It doesn’t ebb in and out of the art world. Neither do curtains.

In Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965), there is a chair on the wall which you can’t use. There is a photograph and a text, all exploring the value systems between the mediation of the chair, the object itself, and the function of language. Which has more importance? The word chair, the actual chair, or the photograph of the chair? The chair has already been used to develop fundamental conversations around conceptual art and semiotics, so it is a great object to reference. A bicycle doesn’t have the same resonance. It doesn’t ebb in and out of the art world. Neither do curtains.

Stuhl III

| © Draiflessen Collection, Mettingen, Foto: Henning Rogge

THE FINAL BID depends entirely on the process of commercial exchange. It is certainly interesting that the historical affluence of Mettingen, Germany, was built upon its residents’ ability to buy and sell. Originally a farming community, only the youngest in each family could inherit the farm, leaving the siblings to find other sources of income. This meant they need- ed to travel to Holland to work as farm laborers. However, over time they realized they could earn much more by selling cloth. By the nineteenth century, an incredible 70 percent of the working population in Mettingen were salesmen, including Clemens and August Brenninkmeijer who founded the company C&A.

BH: You already mentioned that you are interested in the shift in function of objects when they are removed from their previous home, temporarily transferred to a museum, and ultimately given a new home through the auction process. The fascinating thing is how value is attributed to objects that are not receiving much love and attention anymore. The museum is not actively making the chairs more valuable, since they are not refurbished, but because of the change of location people see them with different eyes, and suddenly a chair just standing in the basement becomes interesting again. Therefore I am particularly looking forward to observing the various forms of interaction with your work and the exhibition—not only the act of bidding on chairs, but especially the way visitors interact with individual objects and how they ask questions and hold conversations. For example, true or invented stories can be told about the individual chairs. The exhibition thus adds a new stage to the chairs’ “object biography.” Every object goes through different stages—almost like life stages: from the idea, development, and production to the sale, use, and disposal. To what extent do these various stages play a role in THE FINAL BID?

MP: The stories associated with the chair are important. There are two different narratives I have in mind. There is a generic story of production. The raw materials being pulled out of the ground, the trees being chopped down, the chairs being designed, engineered, marketed, bought, and sold. Then there is a specific story for every chair. Which house did it come from? How old is it? Was it your grandmother’s chair? Was it used for many years and then put in the basement? Has it got little scratches and nicks that tell a story? There’s the journey from the domestic context to an institutional scenario. And the future journey of the chairs onward, back into a domestic environment, or another institution. This is some- thing we will draw out in the installation. The first thing you see will be the work it- self, a kinetic sculpture with objects going up and down. Then the second phase of the visit will explore the histories that travel with the chairs. This is equally important to me. When you start to pull out those narratives and think about what they mean. Most of the chairs entering the museum are unwanted and unloved. So, the question is: “At what point did they become unloved and why?” Probably because a slightly more modern, thus more fashionable, chair came to replace it. Or perhaps somebody died and you just inherited it with a whole load of furniture you haven’t yet got around to selling. I am interested in systems and superstructures. For this installation, I’m not making a sculpture out of chairs; I’m conceiving a framework in which chairs can be shown. A system of reuse. There are, of course, auctions real and virtual, but if they were truly effective, we would buy fewer new products. This is a question of both systems and culture. When I was a child, the dustman would collect your unwanted furniture, put it on the top of the dustbin lorry, and bring it back to their yard to sell it. The money they made from sales was put toward their union to subsidize worker’s holidays. Then the Scouts used to come around door to door to pick up any unwanted goods for their jumble sales. Today, both selling and buying secondhand furniture is difficult unless you own a van. Often people buy new goods, just because they are delivered to their door the next day. There also used to be shops that sold your secondhand goods on commission, so you could actually make money from them. In Britain, such things hardly exist anymore. As we move toward ecological collapse, we hear lots of talk about what we’re going to do, but the reality is that we consume more and reuse less. The systems of reuse I took for granted in the 1970s don’t exist anymore. There will be similar stories in Germany that are both positive and negative, but I am sure that the ease of reuse has got much worse in every country over the last fifty years.

BH: You already mentioned that you are interested in the shift in function of objects when they are removed from their previous home, temporarily transferred to a museum, and ultimately given a new home through the auction process. The fascinating thing is how value is attributed to objects that are not receiving much love and attention anymore. The museum is not actively making the chairs more valuable, since they are not refurbished, but because of the change of location people see them with different eyes, and suddenly a chair just standing in the basement becomes interesting again. Therefore I am particularly looking forward to observing the various forms of interaction with your work and the exhibition—not only the act of bidding on chairs, but especially the way visitors interact with individual objects and how they ask questions and hold conversations. For example, true or invented stories can be told about the individual chairs. The exhibition thus adds a new stage to the chairs’ “object biography.” Every object goes through different stages—almost like life stages: from the idea, development, and production to the sale, use, and disposal. To what extent do these various stages play a role in THE FINAL BID?

MP: The stories associated with the chair are important. There are two different narratives I have in mind. There is a generic story of production. The raw materials being pulled out of the ground, the trees being chopped down, the chairs being designed, engineered, marketed, bought, and sold. Then there is a specific story for every chair. Which house did it come from? How old is it? Was it your grandmother’s chair? Was it used for many years and then put in the basement? Has it got little scratches and nicks that tell a story? There’s the journey from the domestic context to an institutional scenario. And the future journey of the chairs onward, back into a domestic environment, or another institution. This is some- thing we will draw out in the installation. The first thing you see will be the work it- self, a kinetic sculpture with objects going up and down. Then the second phase of the visit will explore the histories that travel with the chairs. This is equally important to me. When you start to pull out those narratives and think about what they mean. Most of the chairs entering the museum are unwanted and unloved. So, the question is: “At what point did they become unloved and why?” Probably because a slightly more modern, thus more fashionable, chair came to replace it. Or perhaps somebody died and you just inherited it with a whole load of furniture you haven’t yet got around to selling. I am interested in systems and superstructures. For this installation, I’m not making a sculpture out of chairs; I’m conceiving a framework in which chairs can be shown. A system of reuse. There are, of course, auctions real and virtual, but if they were truly effective, we would buy fewer new products. This is a question of both systems and culture. When I was a child, the dustman would collect your unwanted furniture, put it on the top of the dustbin lorry, and bring it back to their yard to sell it. The money they made from sales was put toward their union to subsidize worker’s holidays. Then the Scouts used to come around door to door to pick up any unwanted goods for their jumble sales. Today, both selling and buying secondhand furniture is difficult unless you own a van. Often people buy new goods, just because they are delivered to their door the next day. There also used to be shops that sold your secondhand goods on commission, so you could actually make money from them. In Britain, such things hardly exist anymore. As we move toward ecological collapse, we hear lots of talk about what we’re going to do, but the reality is that we consume more and reuse less. The systems of reuse I took for granted in the 1970s don’t exist anymore. There will be similar stories in Germany that are both positive and negative, but I am sure that the ease of reuse has got much worse in every country over the last fifty years.

We need to make it really easy for people to buy secondhand goods, and also to give away or sell secondhand goods. That means taking the goods from their door. How can someone who is old and frail get rid of their furniture or even their clothes? We don’t want them to drive for miles, because that negates any value gained by reuse in the first place.

NR: I think it is obvious that for you the artwork is a way of bringing people into action, of activating them. The installation will only work if people bring us their chairs, and if they want to buy chairs. It is all about people becoming involved.

MP: This is true, and this is why this project is risky. When you build a sculpture, you can control its appearance. With THE FINAL BID, we don’t know what chairs will be offered, so we don’t know how the installation will look. As with John Cage’s systems of chance, we have no idea how the arrangement of chairs will be composed. It’s entirely dependent on the public, both to supply the exhibition and to engage with it, and this is unpredictable.

My ambition with THE FINAL BID is to encourage visitors to change their lifestyles by creating new habits. This is only symbolic at this point, but the installation demonstrates that new habits are possible.

You establish new patterns of behavior through action, not by talking. Using David Kolb’s learning model, firstly you experience the work, then you reflect on its form, then you consider the systems which underpin the work, and finally you actively engage in the process. Only at the point of action do you embed the learning. This relates to a project that I’m curating in King’s Cross, called The Natural Cycle, by the artist Roadsworth. It is a mini-village of roads which helps young children to learn how to cycle. It lets them build a sensibility around the roads; where you give way, how you cross the road, how you turn right, how you turn left, and how you deal with zebra crossings. It familiarizes them with the whole vernacular of the street, the road signage and markings, be- fore they cycle on a real street. If you build certain habits as a child, you tend to keep those habits for the rest of your life. If you’re used to being driven to school every day as a child, you will probably continue to drive. That’s your norm. But if you cycle to school, you are likely to cycle as an adult. Thus, it is essential to establish those habits with children when they are young. This will have a significant impact on our climate. So, The Natural Cycle establishes patterns of behavior through action at a really young age.

In a similar way, THE FINAL BID helps children to reevaluate the assumption that new is good, and to consider whether new should be bad and old is good. I want children to ask their parents, “Why are you buying new chairs? The ones we have

look perfectly alright to me. Are you buying new chairs just to show off to your friends?” Whether we buy old or new is a cultural, not a practical, decision.

BH: There again, the marketing aspect plays a big role. Nowadays, many products are labeled as sustainable and “green,” and at the same time the question arises as to what this actually means and according to which criteria the sustainability of products is evaluated. In many cases, one can certainly speak of greenwashing, that is, giving products an environmentally friendly and responsible image. After all, hardly anyone is aware that our daily consumption of products accounts for the largest share of our personal carbon footprint— and that does not include food, but only products such as clothing, decorative items, and technical devices. From this point of view, it is important not only to create an awareness of the ecological consequences of our daily consumption, but also to establish easily accessible information and assessment criteria so that everyone can make up their own minds. Basically, it’s about doing the right thing and being clear about what the right thing is in order to preserve resources in the first place, right?

MP: Yes, the fundamental principles are to reuse and repair rather than buy new. Let us imagine your fridge breaks down and you need to get it repaired. It costs a hundred pounds to get it repaired, so you think, “Oh, it’s an old fridge, it’s not very efficient. I can get a triple A star fridge and feel really good about my carbon footprint. It’s really easy to buy on Amazon and I don’t need to deal with rogue tradesmen.” The problem is that no one is thinking about the carbon cost of making the fridge from scratch and disposing of the old one. My guess is that the carbon cost of making a fridge outweighs the energy savings throughout its entire lifetime.

BH: There again, the marketing aspect plays a big role. Nowadays, many products are labeled as sustainable and “green,” and at the same time the question arises as to what this actually means and according to which criteria the sustainability of products is evaluated. In many cases, one can certainly speak of greenwashing, that is, giving products an environmentally friendly and responsible image. After all, hardly anyone is aware that our daily consumption of products accounts for the largest share of our personal carbon footprint— and that does not include food, but only products such as clothing, decorative items, and technical devices. From this point of view, it is important not only to create an awareness of the ecological consequences of our daily consumption, but also to establish easily accessible information and assessment criteria so that everyone can make up their own minds. Basically, it’s about doing the right thing and being clear about what the right thing is in order to preserve resources in the first place, right?

MP: Yes, the fundamental principles are to reuse and repair rather than buy new. Let us imagine your fridge breaks down and you need to get it repaired. It costs a hundred pounds to get it repaired, so you think, “Oh, it’s an old fridge, it’s not very efficient. I can get a triple A star fridge and feel really good about my carbon footprint. It’s really easy to buy on Amazon and I don’t need to deal with rogue tradesmen.” The problem is that no one is thinking about the carbon cost of making the fridge from scratch and disposing of the old one. My guess is that the carbon cost of making a fridge outweighs the energy savings throughout its entire lifetime.

Exhibition View Michael Pinsky, THE FINAL BID

| © Draiflessen Collection, Mettingen/Michael Pinsky, Foto/photo: Henning Rogge

BH: This is an interesting example, as I recently saw on Instagram that it is supposedly better to buy a new fridge if the used one is very old. But how do I know that’s true, and how can I take all factors into account and not just electricity consumption?

MP: We have the same dilemma with electric cars. People buying electric cars feel really good about themselves, but if that means making a new car from scratch, how many years do you need to run that car be- fore its lower carbon footprint in terms of fuel consumption outweighs the carbon cost of its production? We were subsidized by governments to move from petrol cars to diesel cars due to the lower carbon output, only to find out later that we had been deceived by companies such as Volkswagen about their cars’ toxic emissions. Then everybody switched back to petrol cars. All new cars, great for the car manufacturers creating massive new markets. Now we are transitioning to electric cars. Again, everyone is disposing of old cars and buying new cars, again fantastic for car manufacturers. The option of getting rid of the private car altogether is rarely considered. It is bad for the market. It is bad for capitalism. It is the same with computer monitors and TVs. Everyone replaced them with the flat-screen ones, and the “fat” old ones got thrown out even though they were still working. I’ve got speakers in my studio that I bought secondhand thirty-five years ago, and they still work perfectly. Technology is one of these areas where people have to buy again and again, as the software stops being supported and the interconnecting plugs become redundant. The manufacturing industry maintains a market where they actively make existing technology obsolete to sell new gadgets.

BH: And creating a sense of lack or need is obviously a big part of it, isn’t it? That constant feeling of need. You need something, and you especially need something new. This feeling is not only conveyed through advertising and trends, but the need is artificially created by products—especially technical ones—breaking down after a certain time. I’m sure you know what this

built-in limit is called . . .

MP: Built-in obsolescence.

BH: Yes, exactly. This also keeps consumption and the exchange of goods at a constant level, because people are forced to buy a new device when the old one doesn’t last for decades but breaks down after a few years. But still, it’s not easy to find information about the carbon footprint of the production—and also dismantling and recycling—of products like furniture. It is not that there is none—the demand for such information and data is actually growing—but there’s really a gap in easily accessible information here. When talking about consumption, primarily food and living costs are considered in studies and surveys of CO2 emissions. I find it interesting that everyday objects like furniture hardly get any attention.

MP: It is because these are not regular monthly purchases; people don’t factor environmental impact into their thinking. However, these products are the lowhanging fruits in the carbon story. Obviously, we can change our diet, but we still need to eat. We can try to fly less and use public transport, but the system is geared against this. Flying is massively subsidized because airlines do not pay taxes on fuel, and many places are inaccessible without a car because public transport is so poor. However, keeping our old furniture or not remodeling our kitchen has no impact on the quality of our lives. We have control over this. We can buy secondhand. We can repair things rather than get rid of them.

MP: Built-in obsolescence.

BH: Yes, exactly. This also keeps consumption and the exchange of goods at a constant level, because people are forced to buy a new device when the old one doesn’t last for decades but breaks down after a few years. But still, it’s not easy to find information about the carbon footprint of the production—and also dismantling and recycling—of products like furniture. It is not that there is none—the demand for such information and data is actually growing—but there’s really a gap in easily accessible information here. When talking about consumption, primarily food and living costs are considered in studies and surveys of CO2 emissions. I find it interesting that everyday objects like furniture hardly get any attention.

MP: It is because these are not regular monthly purchases; people don’t factor environmental impact into their thinking. However, these products are the lowhanging fruits in the carbon story. Obviously, we can change our diet, but we still need to eat. We can try to fly less and use public transport, but the system is geared against this. Flying is massively subsidized because airlines do not pay taxes on fuel, and many places are inaccessible without a car because public transport is so poor. However, keeping our old furniture or not remodeling our kitchen has no impact on the quality of our lives. We have control over this. We can buy secondhand. We can repair things rather than get rid of them.

This is easy to do and significantly lowers our carbon footprint.

NR: And what about art? Are you convinced that artworks can bring people to change their habits?

MP: I’m doing what I can do within my profession as an artist. I won’t have as much impact as a politician or a CEO of a big manufacturing company, but my art can symbolically demonstrate principles. Art is shown in a privileged framework. People go to galleries and museums to think and reflect. You’re not grabbing them on the street, you’re not in a newspaper full of adverts, you’re not in a Twitter feed. The opening of the mind that happens in a gallery or museum is a unique moment that artists have access to. During these reflective moments, people can genuinely absorb information in a creative way, and rethink how they are living their lives. So, artists do have an important role in terms of changing the culture around consumer- ism, because our currency is our culture.

BH: That is a very important point and an intriguing analogy. From a curatorial point of view, our approach from the very beginning was to pursue a thematic issue for the exhibition. The Draiflessen Collection is currently dealing intensively with questions of sustainability and thus also with the ideal of a green museum. The issues you explore in your work naturally fit in very well with this. Would you like to tell us more about which themes and questions are important to you and what interests you as an artist?

MP: Even as a child I took a keen interest in the environment before I knew anything about climate change. When I was about eight years old, the local museum hosted an exhibition sponsored by Scottish nuclear power. It was a pseudoscientific exhibition about nuclear reactors, demonstrating how good they were and how they gave us “free” energy. I was adamantly opposed to nuclear energy at that age. There were no sustainable solutions around waste disposal, and there still aren’t. So, I visited the show with my friends and kept on asking the tour guides difficult questions. We must have looked incredibly precocious at the time, and we ended up getting thrown out. However, we kept on returning until they wouldn’t even let us in the exhibition. I was astutely aware, even as a child, that this exhibition was greenwashing nuclear power. Since then, I have continued with this activism. As an art student, my work was very much in the vein of British Land Art. I was inspired by artists such as Richard Long, Andy Goldsworthy, Kate Whiteford, and David Nash. My work focused on the countryside. But when I moved to London, I started to feel that this approach was a romantic irrelevance. The everyday environment in which most people live is urban, not rural.

I found it bizarre that people drove everywhere in London in cars. This was at a time when the Conservative Party had destroyed the public transport infrastructure. So, I started to map out central London by recording the time it took to drive, cycle, walk, take the bus and the Tube. I designed temporal maps comparing the modes of transport to show how long it took to drive and how ridiculous it was (fig. 4). I showed these hybrid map/prints in a gallery within The Economist building in central London. The exhibition led to a lively discourse around why the existing communications systems promoted the use of the car and the Tube, rather than walking and cycling. In the center of London, riding the Tube can take longer than walking, because you need to descend far underground just to get to the platform. To make the right choices we need to have the right information. At that time there was no data about how long it took you to get from A to B.

There were simply conventional maps in a book, the A to Z, or the Tube map which disregards both time and distance. Of course, Harry Beck’s Tube map is a fantastic piece of design and is easy to use, but it is also a potent and deceptive marketing device.

I explored whether we could change the way people behave with a new data stream based on time. Nowadays we have GPS on our phones, so we can make those comparisons really easily, but back in 1998, this was really difficult to do. Even with GPS, it is only recently that Google and Apple maps have included the bicycle as an option, and this option is hidden so far behind the car, public transport, and taking a taxi that you have to scroll left to see it. Why is the car always the first option when it is such a dysfunctional way to travel through the city? Wouldn’t it be better if they listed the options in terms of speed, with the fastest option first? In the city, the bicycle would leave all the other options well behind.

I explored whether we could change the way people behave with a new data stream based on time. Nowadays we have GPS on our phones, so we can make those comparisons really easily, but back in 1998, this was really difficult to do. Even with GPS, it is only recently that Google and Apple maps have included the bicycle as an option, and this option is hidden so far behind the car, public transport, and taking a taxi that you have to scroll left to see it. Why is the car always the first option when it is such a dysfunctional way to travel through the city? Wouldn’t it be better if they listed the options in terms of speed, with the fastest option first? In the city, the bicycle would leave all the other options well behind.

Michael Pinsky, In Transit (Bike Map) (2000), Vinyl auf Glas, 180 × 100 cm, (Abb. 4)

| © Michael Pinsky, Courtesy the artist

BH: Absolutely. An exciting thought—especially as a cyclist.

MP: The GPS systems only show you how long it takes to drive from A to B, but not how long it takes to park. With all the da- ta they collect in the cloud, this would be easy to provide.

BH: I find it interesting that people are un- aware of how much time is actually spent looking for a parking space, although there are even statistical surveys on this. In Germany, drivers spend an average of forty-one hours a year looking for a parking space—that’s almost two days! (2)

MP: This shows again how all of these things are interlinked. The data exists, but the data is manipulated or obscured to encourage consumption. So, we need art to provide the counternarratives. We live in a neoliberal economy that promotes consumption. Governments are always trying to increase their gross domestic product. Art offers a rare opportunity to counteract that political force, because the narrative that economic growth is good is being sold to us every day. Governments will not pro- mote degrowth, and of course manufacturers will not support this, as they see it as economic suicide. So, who’s going to do it? Institutions such as museums need to host artists who question this current “consume until you eat yourself” crisis that we’re in.

BH: And there we are again with the change in human behavior and the need for a sustainable lifestyle. Because at the moment, Germans are consuming the re- sources of almost three earths on a global scale. Anyone can see at a glance that this is too much: we only have one earth. It is as simple as that. (3)

Obviously, a participatory aspect is an important part of your artistic practice. Instead of just researching data for your works of art, you are pursuing a more collective way of working with people; maybe you raise a question that frames an art project, but people will create the data while interacting within your framework. So it’s more like creating a new narrative together in a way.

MP: It is. People are implicit in this narrative; whether I can change things or not is another matter—one can only try. Some of the visitors to my show at The Economist told me that they would return home a different way from the way they had arrived. That is behavioral change, which is something that is really important in my work. It is behavioral change through action. Firstly, you have to change people’s perceptions; then they need to change their behavior through changing their actions. This is one of the goals of my work. But, of course, I never want to undermine the aesthetic qualities of my work. I am playing that very fine line between something that is visually arresting and important within the cannon of art history, and something which changes people’s behavior. The work could easily slip off the line and become solely propaganda. Maintaining a strong visual sensibility is essential to carrying the narrative of the artwork. It is the powerful visual moment that engages people in the first place. It is what lures people in. Then the narrative is revealed.

Ausstellungsansicht Michael Pinsky, THE FINAL BID

| © Draiflessen Collection, Mettingen/Michael Pinsky, Foto/photo: Henning Rogge

BH: To conclude our conversation, allow me to ask a somewhat heretical question: What is actually the artwork in this exhibition? Is it the idea or the installation? And what about the visitors’ additions?

MP: The framing of the installation within the museum space clearly articulates it as an artwork. This question is more challenging when my installations are in the public realm, where the context is more ambiguous. Engaged practice and relational aesthetics are familiar terms within the sphere of professional art, but not for the general public. However, the journey to the exhibition space at the Draiflessen Collection—through the garden, down the ramp, through the shop, up the steps—provides an expansive threshold which is telling the visitor, “You are going to see an artwork.” So, by the time they get up those steps, they are primed to experience art, even if they are looking at their old chair which was in the cellar a couple of weeks before. Again, this goes back to Duchamp, the framing of the object and the intention of the artist. I have no doubt that this is an artwork. For me, what makes THE FINAL BID intriguing are the engagement and narrative aspects of the work, beyond its physical manifestation. Just hanging a bunch of chairs on wires isn’t interesting to me. It’s everything else that makes the artwork compelling.

_______________________________________________________________

(1) Climart, https://www.climart.info/ (all URLs accessed in August 2022).

(2) Hedda Nier, “So lange sind die Deutschen auf Parkplatzsuche,” Statista, August 2, 2017, https://de.statista.com/ infografik/10532/so-lange-sind-die-deutschen-auf-parkplatzsuche/.

(3) “UNICEF-Bericht: Deutsche verbrauchen fast drei Erden,” Tagesschau, May 24, 2022, https://www.tagesschau.de/ ausland/unicef-ressourcen-verbrauch-101.html.

This interview was conducted by the curators Birte Hinrichsen and Nicole Roth with the artist Michael Pinsky before the opening of the exhibition.

It appeared in the magazine accompanying the exhibition THE FINAL BID.

It appeared in the magazine accompanying the exhibition THE FINAL BID.