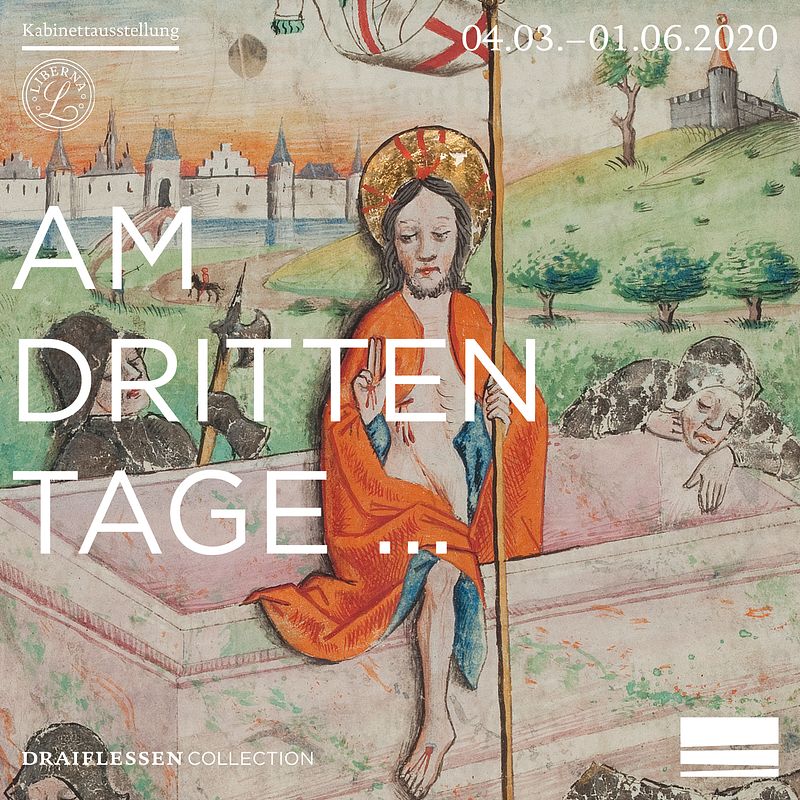

STUDY ROOM | 04.03.2020 – 11.10.2020

ON THE THIRD DAY ...

Resurrection scenes – rendered in vivid colour, some with gold highlights – from books of hours and prayer books from a German private collection will be on display for this showcase exhibition. The medieval/early modern conception of the resurrection of Christ and of the dead must be seen in conjunction with hope for the Kingdom of Heaven and fear of damnation, with both being dictated by one’s own life and its pleasingness to God. This conception finds reflection in thirteen manuscript pages, most of them from German-Dutch speaking regions and dating from the 1430s to the 1540s.

On the third Day ...

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba), Mettingen

Resurrection

The act of the Resurrection itself is not described by the four evangelists. Matthew, alone among the gospels, mentions the guard of soldiers placed at Christ’s tomb (Matt. 27:62–66). Evidence of the desire for a written portrayal of the event, however, is provided by the detailed accounts found in the Apocrypha, the writings not included in the biblical canon. In the early Christian depictions of Christ’s Resurrection, motifs of the women keeping watch at the tomb dominated, with the actual Resurrection merely hinted at by means of the tomb’s overturned lid. Pictorial works in which Christ is shown actually stepping out of the tomb or floating above it are not found in the Western Church until the twelfth century and can be traced back to Byzantine models. These images have recurring attributes, such as the banner of the Resurrection (white with a red cross, or vice versa), the gesture of blessing, the stigmata, the red robe, or the halo. The reason for the late development of this mode of representation was the cultural and historical shift that occurred during the high Middle Ages – and with this shift came the desire to make the sacred visible.

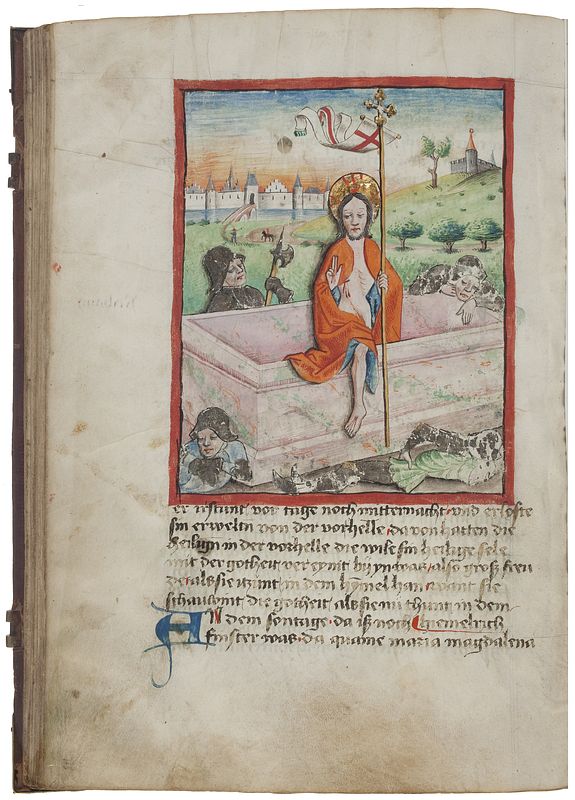

The Passion of Christ, Johannes von Zazenhausen, in German, (Mainz, Worms, or Speyer?), 1464

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba), Foto: Stephan Kube

The Resurrection scene from the Passion of Christ written by the Franciscan Johannes von Zazenhausen († ca. 1380) is executed in light, muted colours and shows Christ, facing forward, stepping out of the tomb. The action goes unnoticed by the soldiers, who, with smiles on their faces, appear to be sound asleep. Smiling faces are encountered on a number of the manuscript’s pages, regardless of the narrative depicted or the mood to be conveyed. These smiles, along with the light colour palette, the burnished gold and silver, and the simple landscapes are distinguishing features of this unknown illuminator’s style.

The iconographic type that depicts Christ climbing out of the open tomb was popular mainly in the German Middle Ages and to some extent was in wide use until the fifteenth century. It emphasises the process of triumphing over death – a final effort, a final sacrifice that can still be considered part of the Passion.

The iconographic type that depicts Christ climbing out of the open tomb was popular mainly in the German Middle Ages and to some extent was in wide use until the fifteenth century. It emphasises the process of triumphing over death – a final effort, a final sacrifice that can still be considered part of the Passion.

This depiction of the Resurrection, a relatively late handcoloured engraving from the southern Netherlands, appears in a Rosary book. The use of such a book is largely founded on a meditation technique that involves devoutly and rhythmically repeating the Rosary prayers with the aid of a string of beads. This practice was already common in medieval monastic circles with salient verses from the Psalms. Laypeople, however, initially confined themselves to repeating the Lord’s Prayer (Pater Noster). With the rise of Marian devotion in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the Hail Mary (Ave Maria) assumed increasing importance.

The reciting of fifty Ave Marias in honour of the Virgin Mary goes back to a Middle High German collection of legends, the Alte Passional from the thirteenth century. The text contains the story of a young man who is advised to honour the Mother of God by reciting fifty Ave Marias in lieu of making her a chaplet of roses. He follows this advice, and when he does, the Virgin appears before him; as he prays, she plucks each prayer he recites, in the form of a rose blossom, from his lips, and weaves the flowers into a chaplet. The Cistercians were the first to add passages from the Life of Christ to the verses of the Ave Maria; this was also done, separately, by the Carthusian monk Dominic of Prussia (1384–1460), who likewise specified a number of Ave Marias: 150. The rhythmic Rosary prayer, still extant in this form today, was formalised by Pope Pius V (1504–1572) in 1569. This manuscript, which is missing eight engravings, contains a total of fifty meditations, with the illustrations of the Life of Christ consistently appearing on the right-hand page (recto) and the prayers on the facing left-hand page (verso). In this image, Christ is seen hovering majestically above the tomb, the distinct style of the manuscript’s illustrations, characterised by fine hatching and shades of blue, green, red, orange, and yellow, on display.

The reciting of fifty Ave Marias in honour of the Virgin Mary goes back to a Middle High German collection of legends, the Alte Passional from the thirteenth century. The text contains the story of a young man who is advised to honour the Mother of God by reciting fifty Ave Marias in lieu of making her a chaplet of roses. He follows this advice, and when he does, the Virgin appears before him; as he prays, she plucks each prayer he recites, in the form of a rose blossom, from his lips, and weaves the flowers into a chaplet. The Cistercians were the first to add passages from the Life of Christ to the verses of the Ave Maria; this was also done, separately, by the Carthusian monk Dominic of Prussia (1384–1460), who likewise specified a number of Ave Marias: 150. The rhythmic Rosary prayer, still extant in this form today, was formalised by Pope Pius V (1504–1572) in 1569. This manuscript, which is missing eight engravings, contains a total of fifty meditations, with the illustrations of the Life of Christ consistently appearing on the right-hand page (recto) and the prayers on the facing left-hand page (verso). In this image, Christ is seen hovering majestically above the tomb, the distinct style of the manuscript’s illustrations, characterised by fine hatching and shades of blue, green, red, orange, and yellow, on display.

Rosary Book: The Passion of Christ, in Latin, southern Netherlands, 1516

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba)

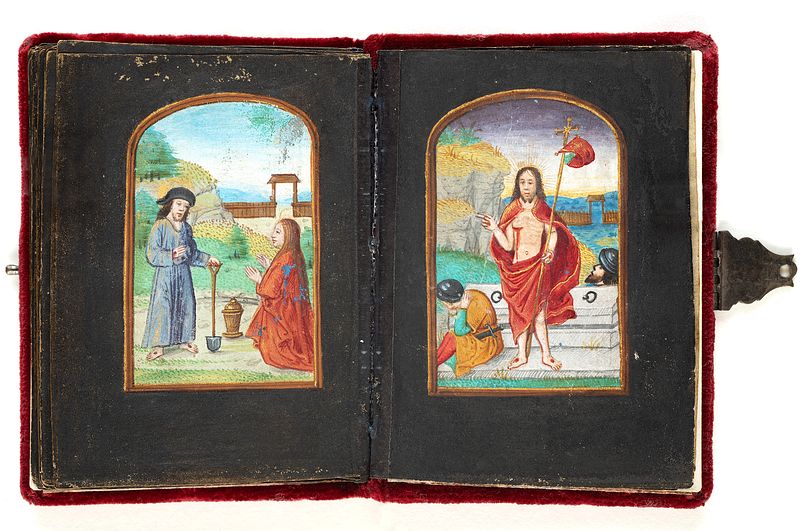

Passion of Christ and Prayer Book, in Latin, southern Netherlands, after 1517

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba)

In this Passion from the southern Netherlands, Christ is shown, as in the Rosary book [4], floating above the closed tomb. On the one hand, the motif makes reference to the Gospel of Matthew (Matt. 27:66, “So they went and made the tomb secure by putting a seal on the stone and posting the guard.”); on the other hand, the closed tomb is an allusion to Mary’s virginal womb. Unlike some of the other Resurrection miniatures, however, here the act of the Resurrection does not go completely unnoticed: the two soldiers in the foreground look up at the risen Christ, their faces filled with astonishment.

The manuscript contains information that points to the place of the commission’s origin: one of the prayers makes reference to the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Wittenberg was the preferred place of residence of the Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise (1463–1525). A patron of the arts and learning, he commissioned works from artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553). It is possible that this manuscript was made for a wealthy member of Wittenberg’s courtly and scholarly community.

The manuscript contains information that points to the place of the commission’s origin: one of the prayers makes reference to the Schlosskirche in Wittenberg. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Wittenberg was the preferred place of residence of the Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise (1463–1525). A patron of the arts and learning, he commissioned works from artists such as Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) and Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553). It is possible that this manuscript was made for a wealthy member of Wittenberg’s courtly and scholarly community.

This manuscript from the Flemish region illustrates the Life and Passion of Christ on fifty-eight pages. With very few exceptions, there is no text. The miniatures are set against a black ground, which lends emphasis to the bold colours of the images. Because the manuscript has a new binding, it is no longer possible to determine whether the illustrations were originally accompanied by descriptive texts. Explanatory passages were not strictly necessary, however, given the straightforward clarity of the depictions. Often, the prayers were inserted after every two illustrations or at the end of the pictorial cycle. Moreover, people at the time were thoroughly familiar with the iconographic programme on the Life of Christ – generally speaking, no further clarification was needed. The Resurrection is placed opposite a depiction of the Noli me tangere, the appearance of the risen Christ to Mary Magdalene. The portrayal of the scene follows the account in the Gospel of John and shows Jesus as a gardener standing before Mary Magdalene; she does not know who he is at first, recognising him only once he reveals himself to her. He prevents her from touching him with the words “Do not hold on to me (Noli me tangere)” (John 20:17) for he had not yet ascended to Heaven.

The Life and Passion of Christ, Bruges (?), ca. 1520–30

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba)

In the medieval and early modern period, the history of the earthly world was seen as ending with the return of Christ as Judge of the World. The individual hope for the Kingdom of Heaven and fear of damnation determined one’s own godly life. With the Last Judgement, the division was final.

The accounts in Revelation (Rev. 4:1–4) and the Gospel of Matthew (Matt. 25:31–33) were central to the development of Christian iconography around the subject. Nevertheless, the depiction of the multi-part Last Judgement appears for the first time only in the eighth century. Typically, it features a top-to-bottom register-like composition with Christ enthroned at the top, surrounded by angels and apostles, and the separation of the blessed from the damned at the bottom.

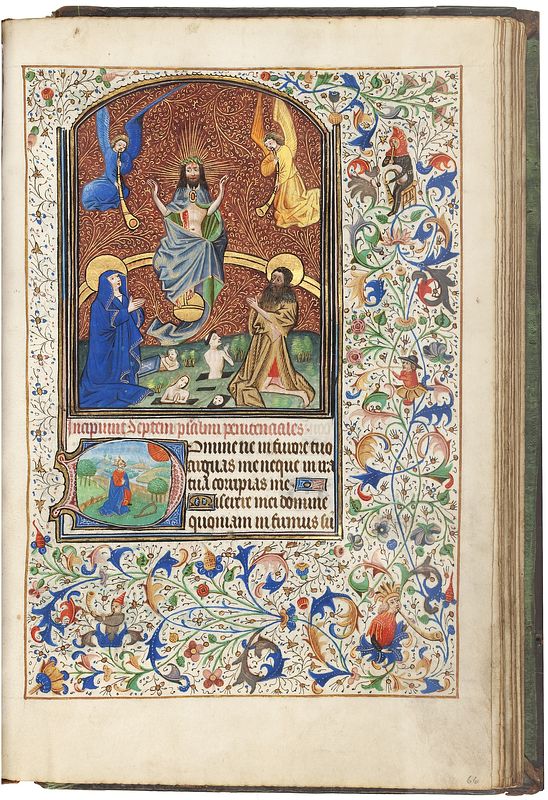

The Last Judgement miniatures presented here all share the same basic compositional principle. Christ the Judge is enthroned on a rainbow, the globe at his feet, while, below, the dead rise from their graves. Angels blowing on trumpets, seen in the upper parts of the images, announce the impending Last Judgement. Christ appears flanked by the Virgin Mary, on his right, and St John the Baptist, on his left; the origins of this three-figure group can be traced back to the Byzantine Deesis (intercession) – according to Christian belief, the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist act as intermediaries between God and humankind.

The accounts in Revelation (Rev. 4:1–4) and the Gospel of Matthew (Matt. 25:31–33) were central to the development of Christian iconography around the subject. Nevertheless, the depiction of the multi-part Last Judgement appears for the first time only in the eighth century. Typically, it features a top-to-bottom register-like composition with Christ enthroned at the top, surrounded by angels and apostles, and the separation of the blessed from the damned at the bottom.

The Last Judgement miniatures presented here all share the same basic compositional principle. Christ the Judge is enthroned on a rainbow, the globe at his feet, while, below, the dead rise from their graves. Angels blowing on trumpets, seen in the upper parts of the images, announce the impending Last Judgement. Christ appears flanked by the Virgin Mary, on his right, and St John the Baptist, on his left; the origins of this three-figure group can be traced back to the Byzantine Deesis (intercession) – according to Christian belief, the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist act as intermediaries between God and humankind.

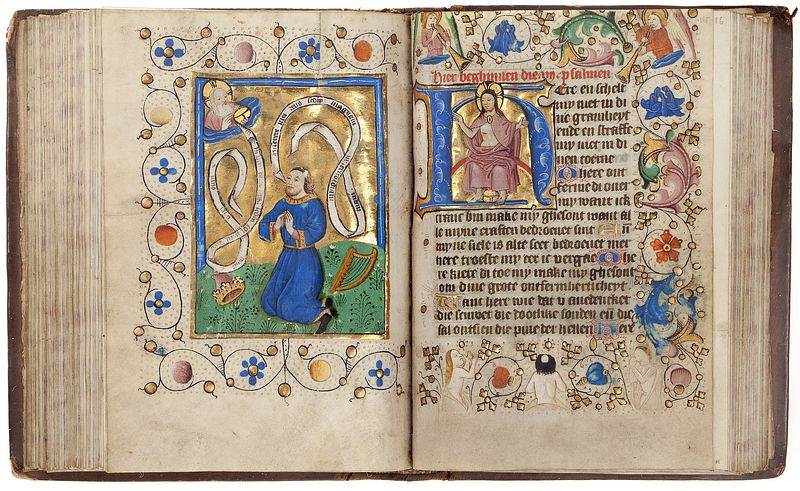

In the two-page spread seen here, the Last Judgement has been integrated into both the D initial and the decorative border. Christ as Judge enthroned on the rainbow appears inside the initial; he is alone, the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist have not been included in the pictorial narrative. The trumpeting angels and the risen dead are embedded in the border at the top and bottom. Artfully fitted into their ornate setting, they are easy to overlook at first glance.

The image on the opposite page shows David – identifiable mainly by his attribute, the harp – kneeling in prayer against a gold ground. David, King Solomon, and Christ himself represent the embodiment of the righteous and the wisdom of the Christian ruler; a direct juxtaposition of the two subjects seen here is therefore not uncommon in Christian imagery.

The image on the opposite page shows David – identifiable mainly by his attribute, the harp – kneeling in prayer against a gold ground. David, King Solomon, and Christ himself represent the embodiment of the righteous and the wisdom of the Christian ruler; a direct juxtaposition of the two subjects seen here is therefore not uncommon in Christian imagery.

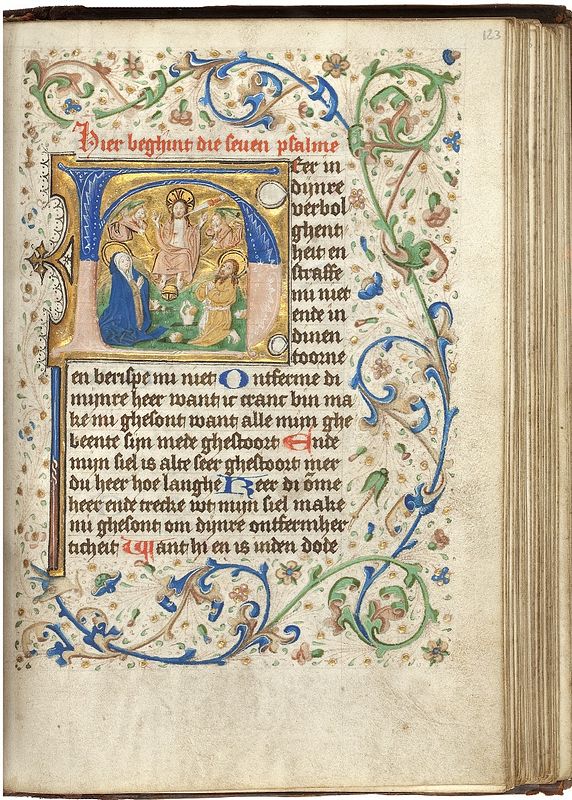

Book of Hours, in Dutch, Zwolle, ca. 1465–75

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba)

Book of Hours, in Dutch, Utrecht (?), ca. 1460

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba)

Dutch manuscript illumination flourished in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, a development that was influenced by a number of factors: the in-vogue preferences of the nobility, the existence of wealthy patrons, the development of panel painting and printing, and the growth of the Devotio Moderna, the lay movement that emerged in connection with the reform activities of Geert Groote (1340–1384). One of the things Groote endeavoured to do was to ensure the Latin texts of the book of hours were translated into the vernacular, thereby making them accessible to lay people. In the early fifteenth century, Dutch manuscript illustrations become increasingly lifelike, characterised by spatial depth, the depiction of material textures, lively landscapes, and an airy heavenly realm.

Utrecht was an important centre and home to a leading illuminator of the time, the so-called Master of Gijsbrecht van Brederode. The book of hours seen here contains six initials that he illustrated with important sacred narratives, including the Last Judgement. Despite its small size, the initial includes all the distinctive elements of the Last Judgement iconography (the three-figure group, the dead emerging from their graves, and the angels).

The colours used in the border decoration echo those found in the initial, lending the manuscript page an appearance of overall harmony. Small dragon heads are seen below the golden bars, a motif common in the Utrecht region.

Utrecht was an important centre and home to a leading illuminator of the time, the so-called Master of Gijsbrecht van Brederode. The book of hours seen here contains six initials that he illustrated with important sacred narratives, including the Last Judgement. Despite its small size, the initial includes all the distinctive elements of the Last Judgement iconography (the three-figure group, the dead emerging from their graves, and the angels).

The colours used in the border decoration echo those found in the initial, lending the manuscript page an appearance of overall harmony. Small dragon heads are seen below the golden bars, a motif common in the Utrecht region.

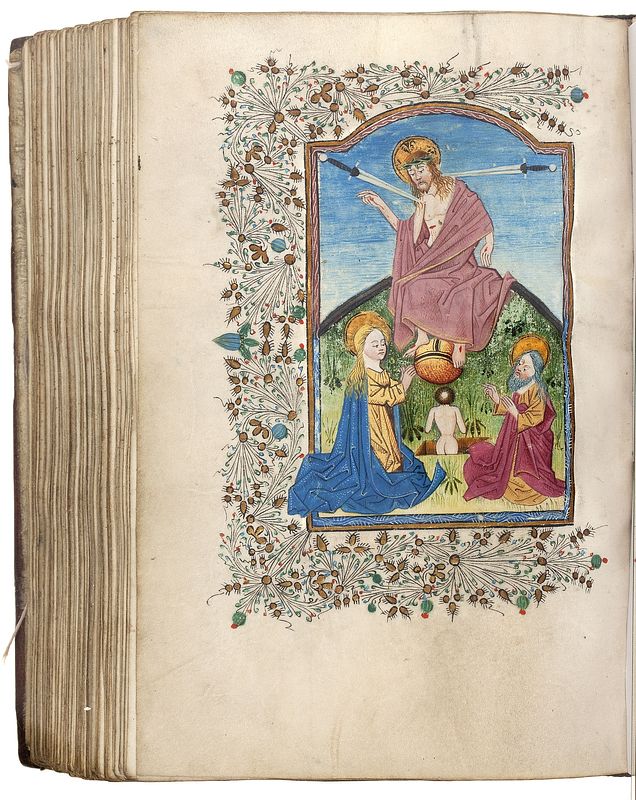

Haarlem was likewise considered a centre of manuscript illumination – and one of its preeminent illuminators was the so-called Master of the Haarlem Bible. Distinguishing features of his style include linear, angular forms and rich, brilliant colours. His border decoration is particularly striking – with its straight and bunched lines, it is delicate and sumptuous at the same time.

These stylistic elements can be seen in the manuscript page shown here, with its brightly coloured presentation of the Last Judgement. In keeping with Last Judgement iconography, Christ is enthroned on a black rainbow that serves as a demarcation between the earthly and heavenly sphere. Reduced to the essentials, the landscape is rendered incompletely in green and features just a single figure risen from the dead. The heavenly world is bright blue and devoid of trumpeting angels. At the level of Christ’s head, the sword of judgement can be seen, a reference to Revelation (Rev 1:16): “In his right hand he held seven stars, and coming out of his mouth was a sharp, double-edged sword. His face was like the sun shining in all its brilliance.”

These stylistic elements can be seen in the manuscript page shown here, with its brightly coloured presentation of the Last Judgement. In keeping with Last Judgement iconography, Christ is enthroned on a black rainbow that serves as a demarcation between the earthly and heavenly sphere. Reduced to the essentials, the landscape is rendered incompletely in green and features just a single figure risen from the dead. The heavenly world is bright blue and devoid of trumpeting angels. At the level of Christ’s head, the sword of judgement can be seen, a reference to Revelation (Rev 1:16): “In his right hand he held seven stars, and coming out of his mouth was a sharp, double-edged sword. His face was like the sun shining in all its brilliance.”

Book of Hours, in Dutch, Haarlem, ca. 1460–70

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba)

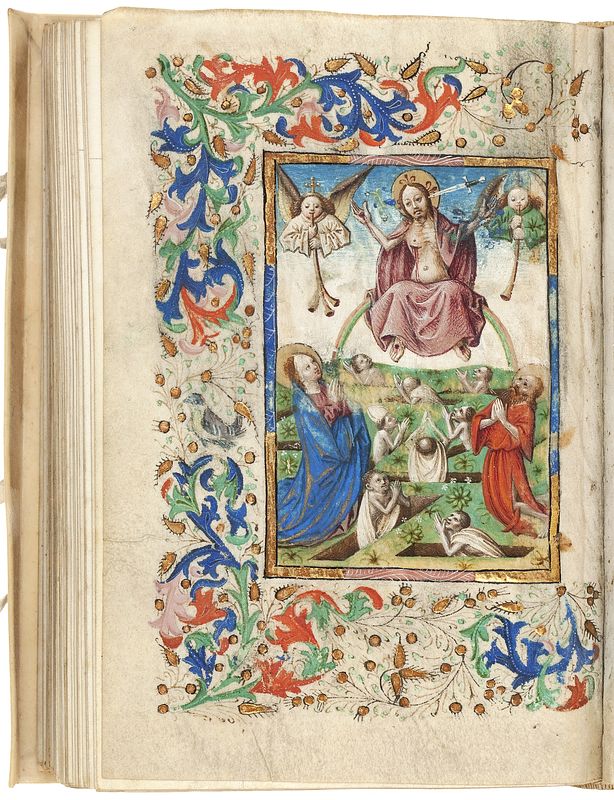

Book of Hours, in Dutch, Haarlem, ca. 1470–80

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba)

Another illuminator well-known in Haarlem was the socalled Master of the London Jason. His name derives from the Historie van Jason (History of Jason), a manuscript he illuminated between about 1475 and 1480. The manuscript on display here contains only four of the original six full-page miniatures.

This rendering of the Last Judgement is characterised by bright colours, lively poses, and a naturalistic approach to representation – these, along with the round faces and softly modelled garments are distinguishing features of this illuminator’s style.

This rendering of the Last Judgement is characterised by bright colours, lively poses, and a naturalistic approach to representation – these, along with the round faces and softly modelled garments are distinguishing features of this illuminator’s style.

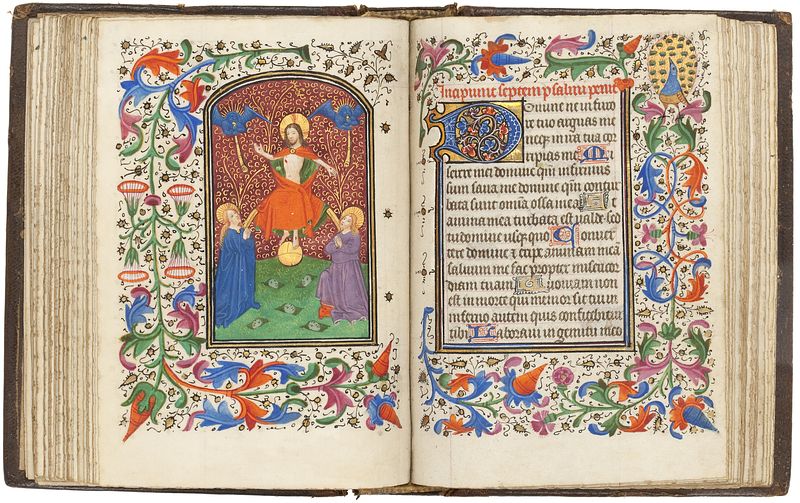

International trade and wealthy merchants fuelled demand for books of hours in Bruges. Consequently, the city became home to another centre of manuscript production, one with a unique style of illumination that differed from the Dutch approach and was not committed to naturalistic representation.

The Last Judgement seen here illustrates the characteristic features of the “new” Bruges style: an absence of perspective, a two-dimensional background, identical faces, and straight drapery folds. The “Masters of the Gold Scrolls” is a name of convenience that encompasses a group of illuminators who were especially active between 1420 and 1450 serially producing scores of books of hours, in most cases making use of existing models. A hallmark of their miniatures is a crimson background decorated with golden scrollwork.

Book of Hours, in Latin, Bruges, ca. 1430–50

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba), Foto: Stephan Kube

Book of Hours, in Latin, Bruges, ca. 1450–60

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba)

The splendid illuminations and the dimensions of this book of hours suggest that the original owner was wellto- do. The ornate miniatures, the numerous illuminated initials, as well as the elaborate ornamentation in the margins point to a variety of influences, including the so-called Gold Scrolls Group, Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390– 1441), and Willem Vrelant (?–1481/82).

Of particular note are the music-making creatures in the border who blend into the colour scheme of the decoration. Their function is a matter of debate among scholars. On the one hand, they are interpreted as adornment and as supplying an element of amusement; on the other hand, they may have been intended as thematic accompaniment to the content.

Of particular note are the music-making creatures in the border who blend into the colour scheme of the decoration. Their function is a matter of debate among scholars. On the one hand, they are interpreted as adornment and as supplying an element of amusement; on the other hand, they may have been intended as thematic accompaniment to the content.

In conjunction with miniatures depicting the eternal life, the question of how to represent the soul is an intriguing one, since no outward description is to be found in the Bible. In the early Middle Ages, the soul was often represented by a bird, whereas in the high and late Middle Ages, a naked, small, usually female figure was typical. The association of nakedness with birth and death goes back to Job: “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return” (Job 1:21).

The angels do not touch the souls with their bare hands but use a cloth; this is not uncommon. On the one hand, the cloth can serve as a symbol of reverence for the person, the object, the receiver, or the giver. This can be traced back to the veneration of the saints and the prohibition against touching sacred objects with bare, unclean hands. On the other hand, the cloth is seen as having a protective function as well as a part in the forgiving of sins.

The angels do not touch the souls with their bare hands but use a cloth; this is not uncommon. On the one hand, the cloth can serve as a symbol of reverence for the person, the object, the receiver, or the giver. This can be traced back to the veneration of the saints and the prohibition against touching sacred objects with bare, unclean hands. On the other hand, the cloth is seen as having a protective function as well as a part in the forgiving of sins.

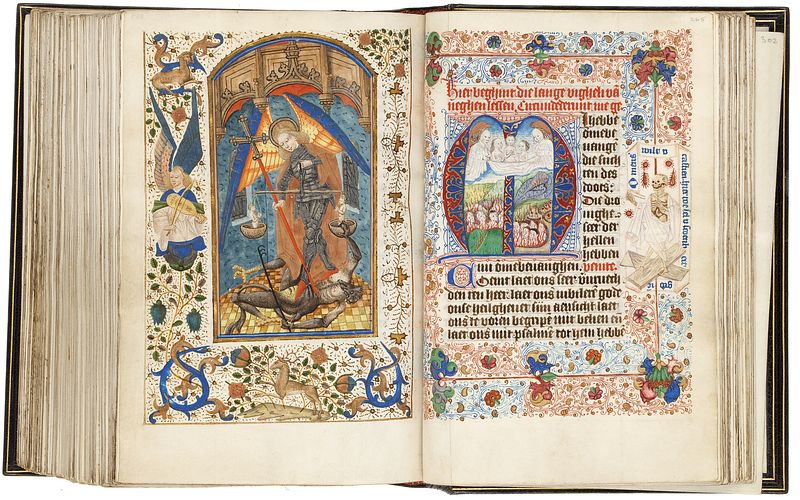

This book of hours illuminated by Master of Beatrijs van Assendelft’s Vita Christi and the Masters of the Delft Half- Length Figures shows Last Judgement events on two facing manuscript pages: on the left, Saint Michael is seen weighing souls, and, on the right, embedded in an M initial, souls are being raised to heaven.

In the depiction seen here, the act of weighing is incorporated into an architectural setting. Michael holds the balanced scales firmly in his left hand. In each scale-pan there is a small soul in human form. With his right hand, Michael simultaneously stabs the demon at his feet, who is in the process of pulling down the “evil” side – the side on Michael’s left – of the still balanced scales.

On the facing page, inside the M initial, three small, naked, redeemed souls, borne in a cloth held by two flanking angels, float through the sky. In accordance with the description in the Gospel of Matthew (Matt. 25:31–33: “and [the Son of man] will separate the people one from another […]. He will put the sheep on his right and the goats on his left”), the lower section of the initial shows, on the right (the Son of man’s left), the damned souls roasting in the jaws of hell. Exuding hopelessness, they look down, resigned to their fates, while the good souls, on the left (the Son of man’s right), direct gazes full of hope towards heaven and the angels.

The striking border decoration, with its red and blue penwork and integrated skeleton, displays the characteristic style of the Masters of the Delft Half-Length Figures:

In the depiction seen here, the act of weighing is incorporated into an architectural setting. Michael holds the balanced scales firmly in his left hand. In each scale-pan there is a small soul in human form. With his right hand, Michael simultaneously stabs the demon at his feet, who is in the process of pulling down the “evil” side – the side on Michael’s left – of the still balanced scales.

On the facing page, inside the M initial, three small, naked, redeemed souls, borne in a cloth held by two flanking angels, float through the sky. In accordance with the description in the Gospel of Matthew (Matt. 25:31–33: “and [the Son of man] will separate the people one from another […]. He will put the sheep on his right and the goats on his left”), the lower section of the initial shows, on the right (the Son of man’s left), the damned souls roasting in the jaws of hell. Exuding hopelessness, they look down, resigned to their fates, while the good souls, on the left (the Son of man’s right), direct gazes full of hope towards heaven and the angels.

The striking border decoration, with its red and blue penwork and integrated skeleton, displays the characteristic style of the Masters of the Delft Half-Length Figures:

Book of Hours and Prayer Book, in Dutch, Delft, ca. 1480

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba)

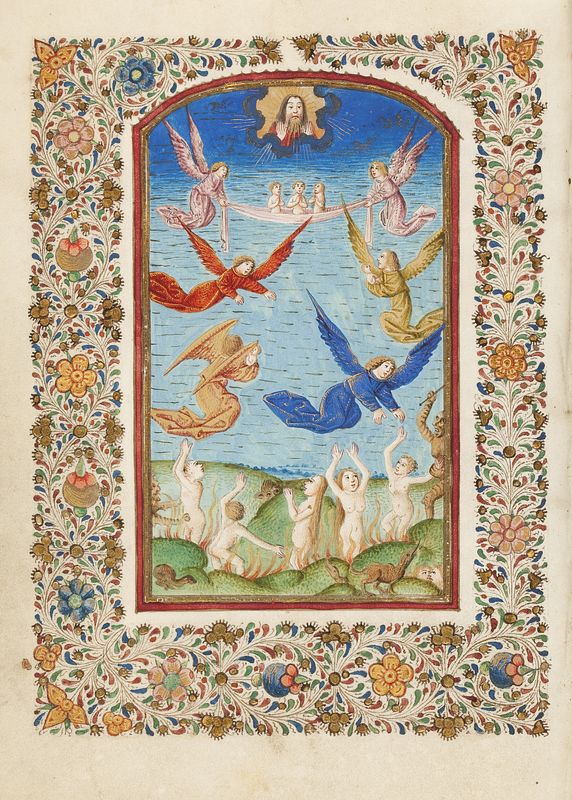

Book of Hours, in Dutch, Delft, ca. 1480, and Leiden, ca. 1490– 1500

| © Draiflessen Collection (Tuliba), Mettingen Ms. 15, Foto: Ruben de Heer

A number of illuminators worked on this book of hours; seven of the full-page miniatures were added at a later time, including the page exhibited here. The illuminator surrounds the miniature with a block-like border, filling out the space with tiny green, blue, and red foliate motifs. The large areas of blue, red, and green tones used in the depiction of the ascending souls set the central image apart from the border.

Placed at the beginning of the Office of the Dead, this fullpage miniature seems remarkably positive, peaceful, and full of hope. God is seen at the top, watching over the interactions between heaven and hell. Directly below him is, once again, the motif of the three small, naked souls in a cloth held by two angels. Additional angels transporting saved souls are seen in the centre of the image, while, in the green landscape that comprises the lower third of the composition, souls raise their arms in hopeful anticipation or, their hands together in a gesture of prayer, wait for the angels to come to their assistance. The attempts of the demons to stop the angels appear to be in vain.

Placed at the beginning of the Office of the Dead, this fullpage miniature seems remarkably positive, peaceful, and full of hope. God is seen at the top, watching over the interactions between heaven and hell. Directly below him is, once again, the motif of the three small, naked souls in a cloth held by two angels. Additional angels transporting saved souls are seen in the centre of the image, while, in the green landscape that comprises the lower third of the composition, souls raise their arms in hopeful anticipation or, their hands together in a gesture of prayer, wait for the angels to come to their assistance. The attempts of the demons to stop the angels appear to be in vain.