DAS FORUM | 04.03.2020 – 25.10.2020

PERSONAL FAVORITES Onkel Canterbumm – How an Advertising Character Made It into the Archive

The storage facilities of the Draiflessen Collection house a vast number of objects and documents that tell a particular story, fill in gaps, or constitute an important discovery. For each installment of “PERSONAL FAVORITES,” which is a series of intermittent presentations, selected treasures are retrieved from storage and put on display with the stories that lie behind them. This year, the staff members of the Draiflessen Collection are presenting a selection of their personal favorites.

The character of Onkel Canterbumm (Uncle Canterbumm) is linked to the magazine “CANTERBUMM erzählt Euch was” (CANTERBUMM Has a Story for You). The primary target audience for these “C&A-Hausmitteilungen für seine kleinen Freunde und Kunden” (C&A Company Newsletters for His Young Friends and Customers) was schoolchildren and their families. Each month during the 1930s and 1950s, C&A customers— and their children—could find copies of the magazine at the packing tables in C&A stores. Initially, the magazine was published from September 1936 until the outbreak of World War II in September 1939. C&A Brenninkmeyer in Berlin was the publisher. The magazine was popular during the prewar years and, after the war, it was produced again—from January 1951 and continuing into 1957—by C&A Brenninkmeyer, now based in Düsseldorf.

Using the example of the Onkel Canterbumm advertising character, this presentation offers visitors a glimpse inside the work of an archivist. Consideration is given to the incorporation of a wide variety of sources on Onkel Canterbumm into the archive of the Draiflessen Collection. It also focuses on the processing of these materials to preserve their original state and on their cataloguing with the aid of the archive database. A glossary of terms with key definitions from the world of archiving runs through the exhibition and provides assistance with understanding the presentation. Highlights among the works on view include issues of the children’s magazine “Canterbumm erzählt Euch was”; the animated advertising film “Komm mit mein Schatz” (Come Along My Darling) by the illustrator Johannes Maria Schneider (1911–2005); and Schneider’s hand-drawn sketches for illustrations published in the magazine.

The character of Onkel Canterbumm (Uncle Canterbumm) is linked to the magazine “CANTERBUMM erzählt Euch was” (CANTERBUMM Has a Story for You). The primary target audience for these “C&A-Hausmitteilungen für seine kleinen Freunde und Kunden” (C&A Company Newsletters for His Young Friends and Customers) was schoolchildren and their families. Each month during the 1930s and 1950s, C&A customers— and their children—could find copies of the magazine at the packing tables in C&A stores. Initially, the magazine was published from September 1936 until the outbreak of World War II in September 1939. C&A Brenninkmeyer in Berlin was the publisher. The magazine was popular during the prewar years and, after the war, it was produced again—from January 1951 and continuing into 1957—by C&A Brenninkmeyer, now based in Düsseldorf.

Using the example of the Onkel Canterbumm advertising character, this presentation offers visitors a glimpse inside the work of an archivist. Consideration is given to the incorporation of a wide variety of sources on Onkel Canterbumm into the archive of the Draiflessen Collection. It also focuses on the processing of these materials to preserve their original state and on their cataloguing with the aid of the archive database. A glossary of terms with key definitions from the world of archiving runs through the exhibition and provides assistance with understanding the presentation. Highlights among the works on view include issues of the children’s magazine “Canterbumm erzählt Euch was”; the animated advertising film “Komm mit mein Schatz” (Come Along My Darling) by the illustrator Johannes Maria Schneider (1911–2005); and Schneider’s hand-drawn sketches for illustrations published in the magazine.

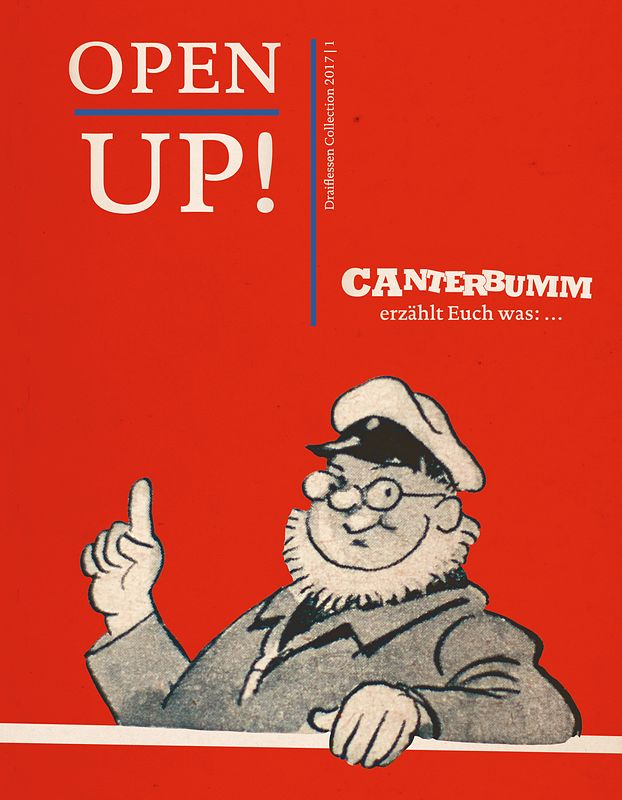

CANTERBUMM visual

| © Draiflessen Collection

Behind the Scenes at the Draiflessen Collection

Who isn’t curious about what goes on behind the scenes of the Collection and Archive department at the Draiflessen Collection?

The current presentation in DAS Forum not only focusses on the likeable Onkel Canterbumm and the works donated to Draiflessen from the Nachlass (personal papers/estate) of Johannes Maria Schneider, it also affords a glimpse into the work being done in the Draiflessen Collection’s archives and storage facilities.

The current presentation in DAS Forum not only focusses on the likeable Onkel Canterbumm and the works donated to Draiflessen from the Nachlass (personal papers/estate) of Johannes Maria Schneider, it also affords a glimpse into the work being done in the Draiflessen Collection’s archives and storage facilities.

Folie aus „Komm mit mein Schatz“, 1934

| © Draiflessen Collection

“Komm mit mein Schatz” – The Film

Filmtisch zum Sichten von historischem Filmmaterial

| © Draiflessen Collection

The tour begins with one of the centrepieces of the collection: the animated advertising film “Komm mit mein Schatz” (Come Along My Darling) from 1934, created by Johannes Maria Schneider. This film was donated to Draiflessen in 2015, along with a number of original drawings. Draiflessen was able to acquire not only the original reel but also the cels used in making the film. As these older forms of film media are highly sensitive and cannot be played on modern devices, they had to be digitised – a process that not only ensures that the film can still be screened but also that it is digitally archived.

Conservation Measures to Preserve Historical Film Material

Digitising the film has guaranteed that at least its content has been preserved for posterity in the “Digital Archive”. But what about the original film material? This, too, had to be preserved. This requires first determining the base material, as this dictates the conditions under which the film material can be stored long term. How is this done?

As most of the staff members from Collection and Archive are archivists or art historians, it is often quite helpful to get an external expert assessment from a restorer. Like archivists and art historians, restorers also specialise in different genres and materials, e.g. paper, wood, metal, painting, film, and photography. Generally speaking, newer reels of film, photographs, and phonograph records are stored in a special climate-controlled room with an average temperature of 18°C, a relative humidity of 45%, and – like all the storage areas at Draiflessen – an oxygen-reduced atmosphere of 15% O2 for reasons of fire safety. These climate conditions are monitored by digital measuring devices but also by an analogue instrument – what is known as a thermo-hygrograph – which measures and records air temperature and relative humidity.

The historical reels are kept in a separate refrigerated space within this climate-controlled room where the temperature is only 12°C – the aim here being to significantly decelerate the natural deterioration process of the celluloid material. The original cels from the 1930s require additional precautionary measures. A rapid chemical test with diphenylamine conducted by the film restorer showed that the cels are made of nitrocellulose – a spontaneously combustible and very fragile material. The cels had to be placed one by one in archive boxes made of acid-free paper; constant air circulation within had to be ensured. In addition, rusty paper clips and similar items needed to be removed – this process is called “enteisen” (the removal of metal) in German.

Thermohygrograph und Archivkartons im Magazin der Draiflessen Collection

| © Draiflessen Collection

The Drawings by Johannes Maria Schneider

Original illustrations for the story “Der Eisbärkönig und das fremde Bärenkind” (The Polar Bear King and the Foreign Bear Cub), issues 1–2, 1954

| © Draiflessen Collection

Drawings by Johannes Maria Schneider from the 1930s and 1950s constitute another highlight of the presentation in DAS Forum. These drawings, which have been framed for the presentation, served as illustrations for short stories that were printed in the Canterbumm magazines. One may chuckle at and cast a critical eye over the motifs and stories, but they also need to be interpreted in their historical context. The issues around the lack of political correctness will not be discussed in further detail here, however, as the focus of this text is the conservation and archiving of the works on view in this presentation.

What is important to bear in mind when dealing with drawings on paper? To start, there is a need for acid-free archive boxes and folders, as has already been mentioned – acidic paper is a consequence of the manufacturing process and chemical additives used in the sizing that have a corrosive effect over time. One problem is that historical documents and drawings are not themselves acid-free, which is why they have to be stored separately and kept under constant climatic conditions. Ideally, room temperature should be between 20°C and 22°C and relative humidity between 50% and 55%. In addition to metal clips, adhesive tapes of any kind must be removed, as these can cause additional damage to the paper over time. Plastic wrappers and protective sleeves are also harmful and not to be used, as microclimates can form inside of them – creating ideal conditions for the growth of mildew. Moreover, the softening agents in plastics do long-term damage to paper. The original drawings for “Canterbumm erzählt Euch was” were placed in mounts for the presentation and secured with almost no direct contact, meaning that once the presentation is over they are ready for long-term archival storage. The paper restorer removed minor impurities on the drawings with a very fine rubber. To prevent new soiling, it is imperative to have a clean environment and, above all, clean hands. Cotton gloves are not recommended for handling paper, as fibres from the gloves can stick to the paper – plus, cotton gloves do not provide a good grip. One alternative is to wear gloves made of nitrile or latex – these prevent deposits of sweat, dirt, and body fat from settling on the paper (often fingerprints only become visible on archival documents or artworks years later). In a final step, the drawings were carefully framed; to protect them from fading and discoloration, the intensity of the lighting in the exhibition was set to 50 lux.

Die Papierrestauratorin bei der Arbeit: Rahmung einer Zeichnung von Johannes Maria Schneider

| © Draiflessen Collection

Draiflessen Collection’s Archive

Covers Canterbumm

| © Draiflessen Collection

The children’s magazines featuring the good-natured Onkel Canterbumm character from the 1930s and 1950s have long been personal favorites of the staff of the Draiflessen Collection’s archive. Accordingly, great was the delight when a number of original drawings for the magazine by the graphic designer Johannes Maria Schneider (1911–2005) were donated to Draiflessen in 2015. An archive is a facility for preserving historical documents of enduring value. Countries, cities, churches, and, in many cases, companies set up archives in order to safeguard the (usually written) traces of their past.

Following the receipt of the original drawings by the Mettingen-born graphic designer Johannes Maria Schneider, the works were placed in acid-free archival folders—the German technical term for this is umbetten (literally “to move to another bed”). Their subsequent preservation under constant climatic conditions in the Draiflessen Collection’s archival storage facility is designed to protect their original state for as long as possible. The preservation of documents, photographs, sound recordings, and film reels is one of the tasks of an archive. Damaged items are restored with care and readied for their placement in archival storage—one such preparatory measure, for instance, is the removal of rusting paper clips. In addition, the archiving of digital data is becoming more and more important given the large variety of file formats and storage media.

Information relating to the Canterbumm documents— including titles, descriptions of content, and keywords—was catalogued with the help of an archive database. Keyword searches allow desired documents to be quickly and easily retrieved. An archive databaseconstitutes an access point to the documents held in the archive. The archive database search functions make it easier to locate documents in response to different queries. The number of relevant documents is narrowed down, for example, by using keywords and categories.

Without the Draiflessen Collection archive, the character of Onkel Canterbumm might possibly have faded into oblivion. The evaluation of historical documents constitutes an essential precondition for remembrance of the past. It was for this reason that the Draiflessen Collection, in 2017, devoted an issue of its “OPEN UP!” series to Onkel Canterbumm and presented the children’s magazines as documents of recent history. When evaluating an archive’s documents, vestiges of the past are compared and interpreted from the perspective of the present. In the process, scattered points of reference fit together, puzzle-like, to create a new overall impression.

Following the receipt of the original drawings by the Mettingen-born graphic designer Johannes Maria Schneider, the works were placed in acid-free archival folders—the German technical term for this is umbetten (literally “to move to another bed”). Their subsequent preservation under constant climatic conditions in the Draiflessen Collection’s archival storage facility is designed to protect their original state for as long as possible. The preservation of documents, photographs, sound recordings, and film reels is one of the tasks of an archive. Damaged items are restored with care and readied for their placement in archival storage—one such preparatory measure, for instance, is the removal of rusting paper clips. In addition, the archiving of digital data is becoming more and more important given the large variety of file formats and storage media.

Information relating to the Canterbumm documents— including titles, descriptions of content, and keywords—was catalogued with the help of an archive database. Keyword searches allow desired documents to be quickly and easily retrieved. An archive databaseconstitutes an access point to the documents held in the archive. The archive database search functions make it easier to locate documents in response to different queries. The number of relevant documents is narrowed down, for example, by using keywords and categories.

Without the Draiflessen Collection archive, the character of Onkel Canterbumm might possibly have faded into oblivion. The evaluation of historical documents constitutes an essential precondition for remembrance of the past. It was for this reason that the Draiflessen Collection, in 2017, devoted an issue of its “OPEN UP!” series to Onkel Canterbumm and presented the children’s magazines as documents of recent history. When evaluating an archive’s documents, vestiges of the past are compared and interpreted from the perspective of the present. In the process, scattered points of reference fit together, puzzle-like, to create a new overall impression.